If you’d like to receive my blog in your in-box each week, click here.

How much easier would life be if it offered us clues to the impact and consequences of our choices? If, as we debated that job or school or partner, a little voice hinted, “little did she know exactly how awful things were going to get…” or “she couldn’t have imagined that this simple decision would be the decisive step in a domino chain of success…,” then making up our minds and making the right choices would be far easier.

It’s the reason for the enduring draw of fortune-tellers and psychics—it’s a seductive promise to offer someone a glimpse of what lies ahead, to shine a light into the vast unknowable darkness of the path before them.

Alas, life doesn’t work that way—but thanks to the literary device of foreshadowing, story can.

Foreshadowing offers hints and clues of events and story developments to come, and it’s a powerful tool for heightening reader engagement, raising stakes, increasing suspense and tension, and developing cohesive characters and plots.

The finesse of foreshadowing is knowing how much to use, and when.

But just like any powerful tool, that sucker can pretty easily get away from you if you’re not careful.

The finesse of foreshadowing is knowing how much to use, and when. Too much and you’re hitting readers over the head with heavy-handed hints that may feel obvious and draw attention to the author’s hand. Too little and you’re likely to wind up with plot or character developments that feel unexplained or out of nowhere. Let’s take a closer look at some common mistakes in each direction, and how you can address them to find just the right Goldilocks balance.

Read more about the types of foreshadowing: "Balancing Foreshadowing"

Too much foreshadowing

Giving away the farm

There’s a difference between teasing in hints and tipping your hand. Offer readers too much information or detail on what’s to come and we’ve got no reason to read it. Consider this scene:

“You’re four minutes late with that report, Jahid,” Carlton barked. “I said I wanted it on my desk at two o’clock sharp.”

Jahid felt his face flush hot; Carlton was the one who’d sent him to pick up lunch for the meeting, knowing it would delay Jahid. His boss was trying to sabotage him—again.

But the tides would soon turn in a stunning reversal of roles.

If this scene and story go on to show how Carlton’s fortunes turn at work and Jahid winds up getting his managerial position when he’s fired, the author has telegraphed much of those developments to us already in that final line, defusing the suspense by telling readers exactly what’s going to happen before proceeding to play it out on the page.

The events of the story that subsequently play out may feel like simply details and logistics—like when the boor at a party tells the punch line of his story before going on to bend your ear for twenty minutes about exactly how it happened.

Hammering the reader/“hanging a lantern”

Too many iterations or repetitions of what you’re trying to foreshadow can weary readers with repetition; too obvious foreshadowing can telegraph what’s to come and defuse suspense. Remember that foreshadowing is a hint—more than that and you’re “putting a hat on a hat,” as they say in comedy: adding unnecessary embellishment.

This kind of foreshadowing faux pas can come in the form of heavy-handed treatment of moments or “Chekhov’s gun” objects that later come into play:

The knife glittered red with the reflected sunset before Dad thrust it into the fish’s belly, slicing smoothly through scale and flesh, dark innards spilling out onto the dock, glistening and wet.

By now readers may be rolling their eyes—”All right, already! We get it! Someone’s getting stabbed with that thing.” You’ve hammered them with the foreshadowing.

Do this repeatedly—or overload the manuscript with too many foreshadowing teases—and you’ve hung a lantern on it as well.

You may also see it as heavy-handed symbolism: “The sky churned with dark, threatening clouds; a terrible storm was coming,” or “the raven eyed me with its cold black gaze, a helpless lizard writhing in its sharp beak.”

It’s the difference between provocative and pornographic: One creates excitement with teasing hints and partial reveals. The other puts it all out on the table (or the desk…or the counter…or really any nearby surface). Remember, foreshadowing offers glimpses of what’s coming, not the full monty.

Clunky foreshadowing

Clumsy, obvious foreshadowing draws attention to itself and can feel ham-handed or manipulative. I like to think of it as the classic musical riff that punctuated melodramatic moments in old movies. (“The knife! It’s missing from the drawer!” Dum-dum-DUM!)

It most often comes in the form of trite, clichéd phrases like “Little did he know he’d picked the wrong house to trick-or-treat” or “She would soon learn just how wrong she was.…” or “Unbeknownst to her, the killer lurked behind the door…”

The instincts are good—to create suspense or a mood or a sense of foreboding. Just pull back a little bit so you’re shading in what’s to come, instead of spotlighting it. Often this is a matter of using indirect foreshadowing, instead of direct: Make your references a little more oblique, for instance in the trick-or-treating example: “A plant on the porch cast shadows like dancing snakes, and Johnny thought about skipping this house—but he didn’t want Amy to think he was a baby.”

Too little foreshadowing

Cryptic or confusing hints

Sometimes this kind of vague, amorphous foreshadowing results because authors “fill in the blanks” of their own story in their head: They know what they mean and what’s coming, so to them the hint makes sense. But readers may lack enough information to understand it, so it comes across as confusing or even irritating, as if the author is fishing or begging for attention.

This foreshadowing faux pas can also be a result of good instincts—an author wanting to hook readers and keep them curious—but in execution can come across like those annoying people who try to garner attention with cryptic social media posts: “So much is happening…I’ll share soon!”

In fiction it may be vague intimations of what’s to come like, “If only she’d known what was coming, she never would have invited him inside”…”I couldn’t have known what my actions would set in motion”…”If anyone learned his secret it would ruin everything…”

Because we don’t know enough detail to plant our feet and make us care, readers may just shrug off these hints or feel manipulated by the author and tune out (the way you know you do when people make those coy “vaguebooking” posts…).

I think of effective foreshadowing as offering readers enough pieces of a puzzle to understand the picture that’s forming, while holding back just one or two key pieces. Orient readers with enough context and specifics so they have a clearer picture, and then hint at what might be depicted on that one crucial interlocking piece.

Deus ex machina

If you fail to adequately pave in later story developments, then they can seem to spring up out of nowhere and feel contrived. If a character’s deceased father shows up later in the story, for example, you have to lay the groundwork for that appearance earlier or it feels “ret-conned” (retroactive continuity): a contradiction or unjustified alteration of established facts or story circumstances.

Make sure you drop some breadcrumbs that will later make his return seem plausible: For instance, if his family thought he died in the World Trade Tower attacks on 9/11, then it might make sense that no body was recovered. Perhaps he was identified by a personal belonging in the rubble—an engraved class ring he wore every day; you might drop a mention elsewhere in the story that he’d lost weight before his death to justify the ring coming off his hand in his escape; and plant other foreshadowing seeds that pave in the reasons for or fact of his disappearance and eventual return.

Overly “quiet” scenes

Scenes that lack suspense or stakes can feel flat and stall momentum—but sometimes they’re necessary, for instance in the setup chapters of certain stories that establish the character’s status quo or starting point, their comfortable existence that’s changed by events to come.

Especially at a story’s beginning, this can hamper readers’ engagement and weaken the hook. Let’s say your protagonist develops precognition, the ability to know the future, that destroys her family and friendships. That may not happen until later in the story, and first we need to see how much she stands to lose from what turns out to be a terrible gift.

Well-used foreshadowing can set that hook even amid a happy, complacent scene of her contented life, before she develops her abilities:

I imagined future holidays, when Geraldo and I were old, the kids beside us on the sofa instead of in an excited sprawl on the floor, and their kids—our grandkids—in their place at our feet around the tree. The glimpse into our family’s future warmed and comforted me, softening the pang of nostalgia at the thought that this might be the last year I’d witness their pure childish delight before they outgrew it.

Something like that both establishes the stakes—how much the protagonist cherishes his family—while planting a subtle seed indirectly foreshadowing his actual ability to see the future and the losses to come that can insert a needed thread of microtension or unease into the scene, even if below the readers’ conscious radar.

#

Foreshadowing well is an art and a skill, requiring a deft and deliberate hand to find the right balance—as well as a keen understanding of how to use the various types of foreshadowing and how to smoothly weave it into your story.

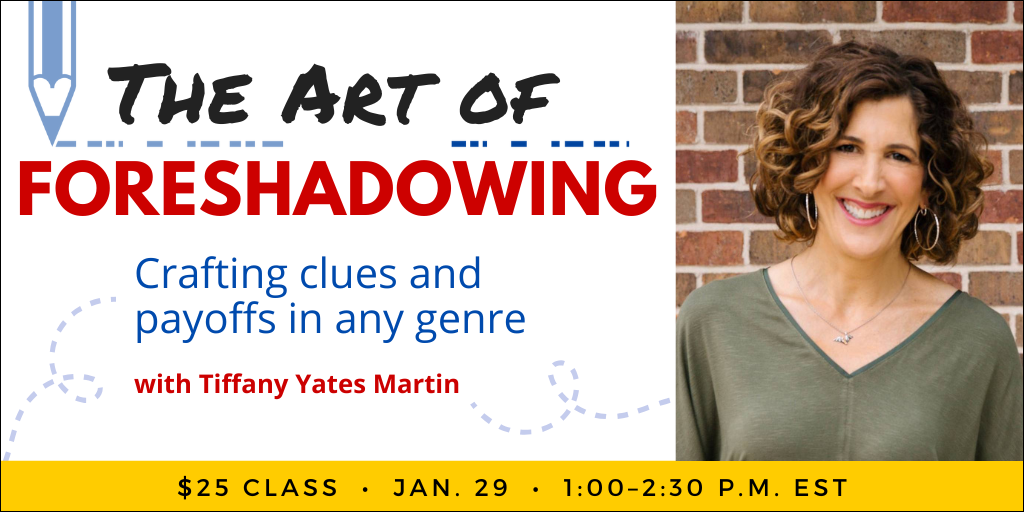

If you’d like to dive deeper into the topic, join me and Jane Friedman Wednesday, January 29, for my brand-new online course, “The Art of Foreshadowing.” (1-2:30 ET, $25 with video playback available to attendees.) If you’ve struggled with using foreshadowing effectively, join us to learn foreshadowing types, elements, and techniques (and avoid common foreshadowing faux pas) to equip you to use this potent tool of suspense authoritatively and with confidence to invest readers deeply in your stories.

Let me hear from you, authors—what foreshadowing struggles do you have in your writing? What stories—books, movies, TV—have you seen use it well to draw you in and whet your appetite?

If you’d like to receive my blog in your in-box each week, click here.

4 Comments. Leave new

Another great post, thank you. I believe that I handle foreshadowing pretty well, but that isn’t to say that it’s easy. I’ve reread my drafts and found most of what you list above. It’s a moment when I then write a rather comical note to myself. It’a a part of writing that I love, and it’s a part of my editing process to check any existing foreshadowing or to add it when needed.

I have, sadly, seen all of your poor examples in published books. I’ll groan and think, “Why did no one say anything before publication?”

On a more positive note…

Some, for me, often goes unnoticed by the conscious mind, instead planting a seed that’s like an itch I can’t scratch, a tension (microtension, maybe?) that eats away at me. A sense that a particular thing is going to happen, but not being certain why I think that. Other times, I believe it’ll happen based on what I perceive as foreshadowing, but the author simultaneously plants doubt in my mind.

I consider myself pretty good at spotting it, yet some of my favorite books, at the least, left me uncertain. In the end, there’s a gasp, admiration, and in some cases, tears. A few that come to mind are, The Upside of Falling Down, A Day Like This, Bone River, The Ivy Tree, and The Life I Stole.

Thanks, Christina. You’re right–foreshadowing isn’t always easy. I often see usage that draws attention to itself or risks pulling readers out of the story, or on the other end of the spectrum, inadequate foreshadowing that makes later developments feel a bit unpaved-in. And I agree that it can sometimes be easier/smoother to go back after you’ve drafted and figure out where you need foreshadowing, what kind, how much.

Your analysis of it in other works is always my favorite (and in my view most powerful) way to really understand and master foreshadowing, or any craft element. For this course, as I was creating it, I went back to reread a lot of books I’d read before, which makes it much more apparent what foreshadowing elements are used. (And a fun game to spot where and how. 🙂 ) I’ve been watching movies and shows with an eye toward it too.

Thanks for the recommended reads! I always appreciate adding good books to my TBR list.

I can’t say I have yet intentionally worked with foreshadowing, but I appreciate its role. I am slowly learning about the art, craft, and skills of writing. So, this piece was really helpful.

I look forward to your class next week and learning more.😊

I’m guessing you have without realizing it, Emily–it’s often intrinsic in laying breadcrumbs to set up later story and character developments–but you may not have used more overt types. I’m glad this post was helpful–looking forward to seeing you in class!