If you’d like to receive my blog in your in-box each week, click here.

Reveals are some of the sexiest story devices an author can employ to hook readers and create stories that get people talking.

But they are also among the more challenging storytelling elements to pull off. An anticlimactic reveal can leave readers underwhelmed. An obvious one disappoints if readers feel they’ve outsmarted the characters or are a step ahead of the author. And a cryptic one can simply leave readers confused and frustrated, giving up on your story.

How do you use this potentially potent device effectively to create strong hooks and enhance your story, while avoiding the many traps inherent in them?

Understanding Reveals

The first step is to define what a reveal actually is, as it’s a term used fairly broadly. A reveal in its usual connotation is the unveiling of some unknown or unexpected information or event in a story.

But it’s also often shorthanded to refer to that information or happening itself—both the springing of the HGTV makeover on the home owner, as well as that makeover itself.

Underneath the broad umbrella of reveals you will also find secrets, mysterious pasts, twists in the plot that may be unknowns, as well as revelations to the reader, the protagonist, other characters, or any combination of these.

But a reveal doesn’t mean any unknown or concealed element of the story, and it’s different from simple story questions and suspense questions. Those belong in every story, whereas forcing reveals in a story that doesn’t need them may distance readers, diminish impact, and bog down momentum.

A reveal doesn’t mean any unknown or concealed element of the story, and it’s different from simple story questions and suspense questions.

A reveal also isn’t a plot twist in the sense of something unexpected abruptly happening to characters—that’s simply an unforeseen development characters must navigate. For a twist to fall under that classification it has to result from something previously unknown and hidden in the story being revealed, whether from the characters or the reader—and not every story calls for or benefits from that device either.

A reveal in the sense that we’re defining it belongs in your story only if the concealment and revelation of whatever it entails is directly germane to the story, essential to how it unfolds.

That means, for instance, that an unknown piece of information or secret is intrinsic to a character’s choices, actions, and arc, as in Liane Moriarty’s The Husband’s Secret, where the titular secret is the cause of every other character’s storyline and arc.

Or it means that it is essential to the plot or story itself, as in Colson Whitehead’s The Nickel Boys, where the main reveal foundationally shifts readers’ understanding of the story and what it was actually about.

Or it may mean it’s the foundation of the story or character stakes, as in Charmaine Wilkerson’s Black Cake, when the main characters’ deceased mother’s will reveals a secret past and identity that the siblings are desperate to discover—and the fallout that changes their lives.

Using Reveals Effectively

Reveals feel cheap and devicey when they are used simply to spice things up, to try to hook readers with an unnecessary mystery or inorganic plot development. Readers sense the manipulation of a reveal used this way and they tend to fall flat.

If something doesn’t need to be a reveal for a reason essential to the story, then you often gain much more impact from simply weaving the information into the story straightforwardly.

If something doesn’t need to be a reveal for a reason essential to the story, then you often gain much more impact from simply weaving the information into the story straightforwardly.

For instance, let’s say your character’s brother died in high school because she refused to pick him up from a party because she was on a date with a boy she had a crush on, and she’s haunted by guilt and remorse ever since, feeling her selfishness killed him.

That’s a mighty big scar, and if the main story, for example, involves her stuck in her dead-end job in her dead-end hometown, keeping romance at a distance, then that backstory is clearly germane to why she’s where she is at her point A. Readers need to know what shaped her into who she is when we “meet” her to fully understand what’s holding her back from whatever her true goals and dreams are—otherwise her actions and choices may feel confusing, unmotivated, or cryptic.

If she meets a love interest and keeps sabotaging things with him, we need to understand why, or stakes may not feel high, and we may lose our investment in her.

In a case like this, perhaps the impactful reveal is the one she has to make to her new love interest, if she’s to have a hope of moving forward in her life, rather than to the reader. Reader investment in her and the story is likely to actually be much higher if we know her full history all along.

One reason reveals can be hard to talk about and hard to master is that they are so broad and varied that it’s impossible to delineate an easy set of guidelines or checklist to apply to all reveals. They are case-specific, and often need to be assessed in the context of the entire story as far as how to pave them in, how well they work, and how to unveil them.

But here are a few general guidelines that may be useful in using reveals effectively.

Techniques and Tips for Successful Reveals

- Determine what information or event(s) you are keeping secret and from whom (protag, reader, other characters). Now ask yourself why, and be really honest. Is it because you are trying to hook readers, keep them guessing with a tasty mystery, or shock them with an unexpected plot development? (If so, reconsider keeping the info secret.) Or is concealing that info truly essential to the story or character arcs? Why/how?

- Even if you do determine a reveal is necessary, make sure you build in the necessary context and foundation for the revelation of the info/event to reverberate for the characters, plot, and reader. That means we need grounding in who these characters are, what they want and what drives them, and what’s at stake. Without that, we don’t invest in your character’s “tragic secret” or hidden agenda, because we don’t know enough to care. Reveals where everything is a mystery simply seem cryptic or coy and leave readers feeling frustrated, confused, and unaffected.

For instance, let’s say your character is a woman who lost her entire family in a fire. To try to conceal her whole past from readers is too much, and counterproductive—it’s directly germane to who she has become as a result and her journey in this story (presumably), so it’s essential that we know about it. But perhaps you keep one facet as a reveal—for instance, maybe she had time to save only one child and chose her youngest, who nonetheless died of smoke inhalation, and the guilt of her actions haunts her in this story.

Because readers know of the rest of the story—that she lost her whole family—we understand enough to grasp her state and situation in this one. And you have enough context to be able to subtly misdirect and conceal that single shameful factor without it seeming manipulative or coy.

Having enough context on reveals is the difference between the anticipation you feel at finding a beautiful gift-wrapped box under the tree or handed to you by a dear friend, versus the confused wariness of discovering a plain brown one left on your doorstep.

- Pave in the clues. What makes reveals so delicious is how they directly engage readers and make them a part of the story—but you have to give us the breadcrumbs to follow.

Even in stories with shocking twists, like Sixth Sense or Fight Club, part of the delight for viewers/readers is going back through and seeing the clues we missed the first time. Much of the skill of laying the groundwork for these reveals lies in hiding those clues in plain sight, giving readers the information but weaving it in so subtly and organically to the story that most don’t realize until going back for a second read how the author was laying every stepping-stone that led inevitably to the reveal.

- When will sharing the concealed information/event (and to whom) have maximum impact on the characters and story? For instance, Moriarty reveals the actual husband’s secret to his wife and the reader relatively early in The Husband’s Secret, because her knowing it is directly germane to her actions and choices that follow, and our knowing it adds stakes and impact to the other main characters’ storylines.

In Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl, readers learn Amy is alive fairly early in the story, because that jacks up stakes for us and is essential to the unfolding of the plot; Nick learns it not long after, which heightens stakes and urgency for him and is intrinsic to how his story develops; but no other characters know it until late in the story, because that discovery is key to the resolution of the plot.

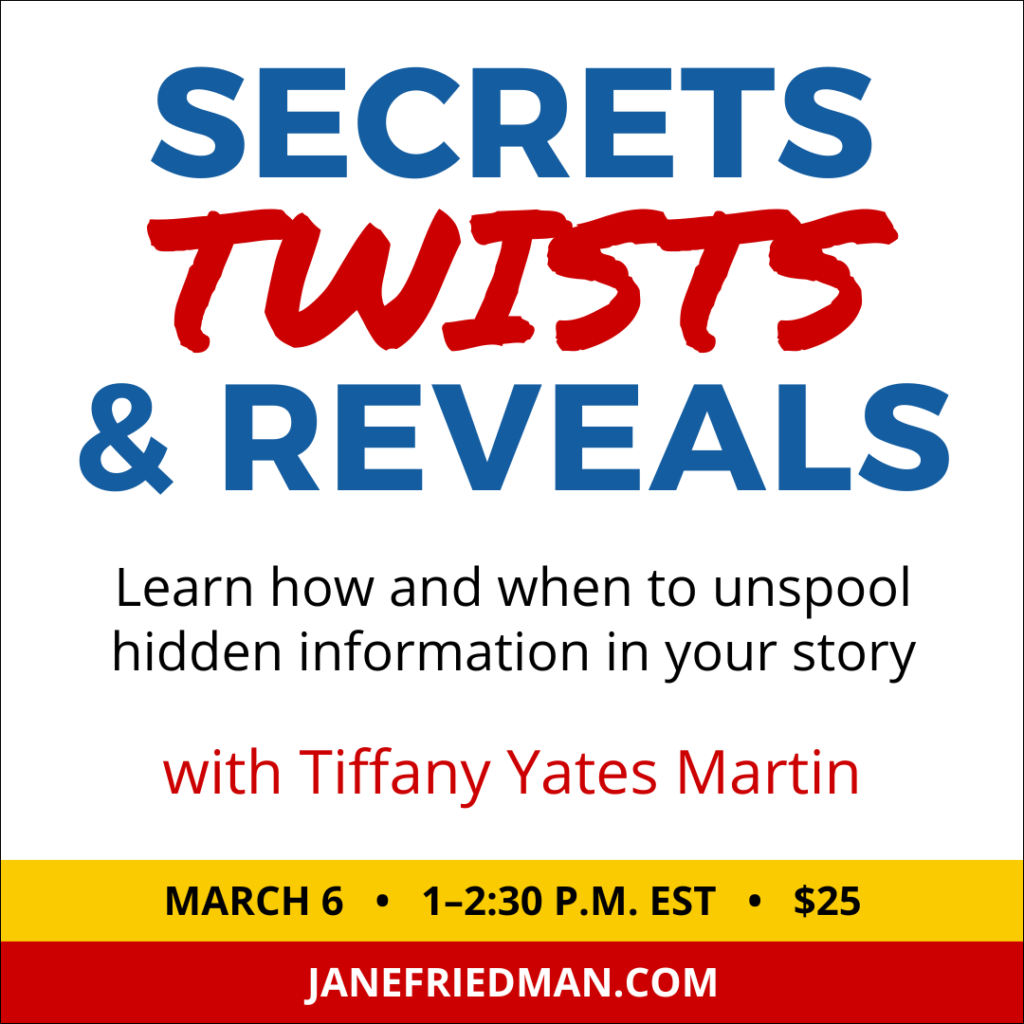

If you want to know more about skillfully using reveals, join me and Jane Friedman Wednesday, March 6, for my upcoming webinar “Secrets, Twists, and Reveals“ ($25 with video playback). I’ll be digging deeper into these and many other elements of creating successful reveals, with lots (and lots and lots) of examples to illustrate the concepts.

If you’d like to receive my blog in your in-box each week, click here.

2 Comments. Leave new

Your comments have made me consider whether I’ve left too big of a bread crumb in chapter one. While a mysterious letter is a good hook, it may be too revealing to the reader for what is meant to be a surprise near the end.

I look forward to the webinar on March 6th.

It’s so hard to gauge it ourselves, when we know all the mysteries. Glad you’ll be in the course! I think it’ll be a useful one.