If you’d like to receive my blog in your in-box each week, click here.

Michael Peterson is a violent murderer who killed his wealthy wife when she found out about his sordid extramarital affairs with men.

Or he is a loving husband and father, the wrongly accused victim of a corrupt justice system and a DA with a personal grudge against him, deeply mourning the unexpected death of his beloved wife, fending off unjust murder accusations.

Or he is a con man and liar who has spent years—decades—manipulating his family and others for his own ends…but not a murderer.

Michael Peterson—the lead character in the miniseries The Staircase, based on a real person—may be any of those things…and potentially all of them to some degree.

The hubs and I recently got sucked into the fictionalized HBO Max retelling of a real-life case in Durham, North Carolina, in the early 2000s, which is based on a French documentary miniseries about it that started filming during the lead-up to Peterson’s trial for the murder of his wife and continued through 2017.

Here are the basic facts of the case: In the early hours of a morning in 2001, Michael Peterson called 911 and reported in a panic that he’d found his wife, Kathleen, at the bottom of a staircase in their home, unconscious. He hung up, then called back minutes later to report that she was no longer breathing.

The walls were heavily splattered with blood. The autopsy later showed unexplained lacerations on Kathleen’s body consistent with a beating and fractured thyroid cartilage that suggested strangulation—but no murder weapon was clearly indicated nor found on the premises. Cause of death was reported as blood loss.

By every report of friends and family, the two were immensely happy together, with an uncommonly close blended family. They were both successful—Michael as a novelist and columnist, Kathleen as an executive with Nortel.

I’m not usually a true-crime aficionado, but we’re only four episodes in and we’re hooked hard. The story is brilliantly structured and told, the screenwriters peeling the onion a little at a time and keeping readers just enough in the dark to create a fascinating layer cake of suspense—largely because of the way the story is told: its perspectives.

What Is a Story’s Perspective?

When we consider the perspective a story is told from, generally we think of several main areas: the POV or voice of the story, the protagonists’ perspectives, and the author voice and approach.

When we consider the perspective a story is told from, generally we think of several main areas: the POV or voice of the story, the protagonists’ perspectives, and the author voice and approach.

But The Staircase layers in so many other strata of perspectives to unspool the story, starting with other characters’:

- The inciting event itself—Kathleen’s death—and its immediate aftermath is revealed through the drunken eyes of their second-oldest child as he stumbles back home after a night out with a friend to find emergency vehicles strewing their yard, his stepmother bloodied and dead at the bottom of the staircase, and his father a shocked, sobbing wreck in the kitchen.

- The police who report to the scene have a different perspective—there is too much blood; Kathleen shows evidence of lacerations. Michael is an immediate suspect.

- Michael’s family—including Kathleen’s sisters—rally staunchly around him…until Kathleen’s daughter breaks away with her aunts and turns against him, sure he is guilty after being shown leading evidence by the DA.

Then the storytellers layer on even more perspectives that become part of the story itself and how it’s told:

- The French documentary team becomes part of the story, purporting to take an objective perspective. And yet it’s quickly evident that each of the filmmakers brings their own slant and wants to tell the story in a way that favors their individual perspective. The screenwriters viscerally show how their choices—a camera angle, an included or deleted scene, where they make the cuts in edits—affect audience opinion.

- The DA assigned the case paints a clear picture of homicide—yet we also learn he has a personal ax to grind against Michael, who writes columns critical of his job performance. His assistant is a highly traditional and conservative woman Southern woman who presents Michael as a deviant and a manipulative liar.

- Michael’s lawyer is spinning his own version of the story, one that paints their loving but untraditional marriage; Kathleen as suffering a tragic accident under the influence of alcohol and Valium, as was her habit; Michael as a grieving bereaved husband trying to care for his family amid wrongful persecution.

- Michael’s may be the most ambiguous perspective of all. We see his version of events, certainly: Having had too much to drink, his wife kisses him good night to go work, and he later finds her crumpled at the bottom of the stairs. But Michael is a bit of a cipher to us, painted only through his actions, reactions, and interactions. We are not privy to his inner thoughts directly. We are not privy to the actual events that happened. We have to piece it together along with all the other players in the story. And yet little by little the storytellers pull back the curtain on elements of Michael’s past and character that continually shift viewers’ understanding of him—and their opinions.

And finally, the storytellers layer in one last perspective: their own, in choosing each perspective and what to reveal when, and in how they unspool it. Part of the story is set in 2017, when we see Michael is free. Even as the main 2001 storyline unfolds, even as Michael is convicted and sent to prison, this knowledge raises even more questions in viewers’ minds: What happens? How does he get released?

And of course the uber-question: Is he guilty?

How Storytelling Affects the Story

When we’re planning our own stories, so often we focus on the main elements of the story itself—the characters, the stakes, the plot—that we may not think about how the storytelling itself impacts the reader’s investment, impressions, and opinions. But it’s a powerful tool to consider.

Without all the varying perspectives, The Staircase is just a straightforward true-crime procedural story, not uninteresting in its details and players, but pedestrian.

It’s the storytelling itself—the perspective, the structure—that elevates it. What lens the storytellers filter events through. What they do and don’t reveal to readers and to other characters, and when.

Considering multiple storytelling perspectives is a dazzling, daunting balancing act, an omniscience of awareness that’s among the hardest skills for a writer to learn.

As the author, consider not just the protagonists’ perspective and point of view, but those of the other characters and how they affect the story. Consider the way you tell it—the chronology, the structure—and what impact it may have on readers’ impressions.

As the story creator you have to take multiple perspectives simultaneously—all of these, and also the reader’s. What might they make of the story based on how you present it? How can you orchestrate their reactions to create the effect you want? It’s a dazzling, daunting balancing act, an omniscience of awareness that’s among the hardest storytelling skills for a writer to learn.

The Power of Storytelling

As the creators of The Staircase peel the onion on events and character relationships, there are backstories upon backstories, each of which affects the characters’ perspectives, actions, choices. Each of which spins our impressions in a new direction.

Every character’s involvement and perspective and actions shift the story being told and what readers believe to be true, creating much of the stakes and suspense of this taut story as the screenwriter expertly peels back layer after layer to uncover deeper and deeper truths and questions.

The result is a complex stew that constantly reveals new flavors and ingredients as the story unfolds. The basic plot, sensational on its own, gains even more impact and draws readers in more deeply by virtue of the way it’s told, keeping readers as much at the mercy of what is revealed as much as are the jurors in the case, the public, and even the players directly involved.

Readers (and viewers) are influenced by what we are told and shown, and through whose eyes, with what slant. This is how propaganda works. It’s how advertising works. It’s how politics and the law work. Frankly it’s how most relationships and human interactions work. Who tells the most convincing story? It’s the power you wield as the author of the story, and a potent ingredient of its originality and voice.

We’re only partway through The Staircase, and I have a feeling viewers are never going to definitively know whether Peterson actually killed his wife.

But that’s not the point—the journey is, and its effect on us, as the viewers: how it repeatedly draws us back to it episode after episode. How it keeps us hooked and guessing all the way through. How it continues to play in our minds between episodes. How we feel about it. All that is a result of the storytelling as much as—perhaps more than—the story itself.

If you’d like to receive my blog in your in-box each week, click here.

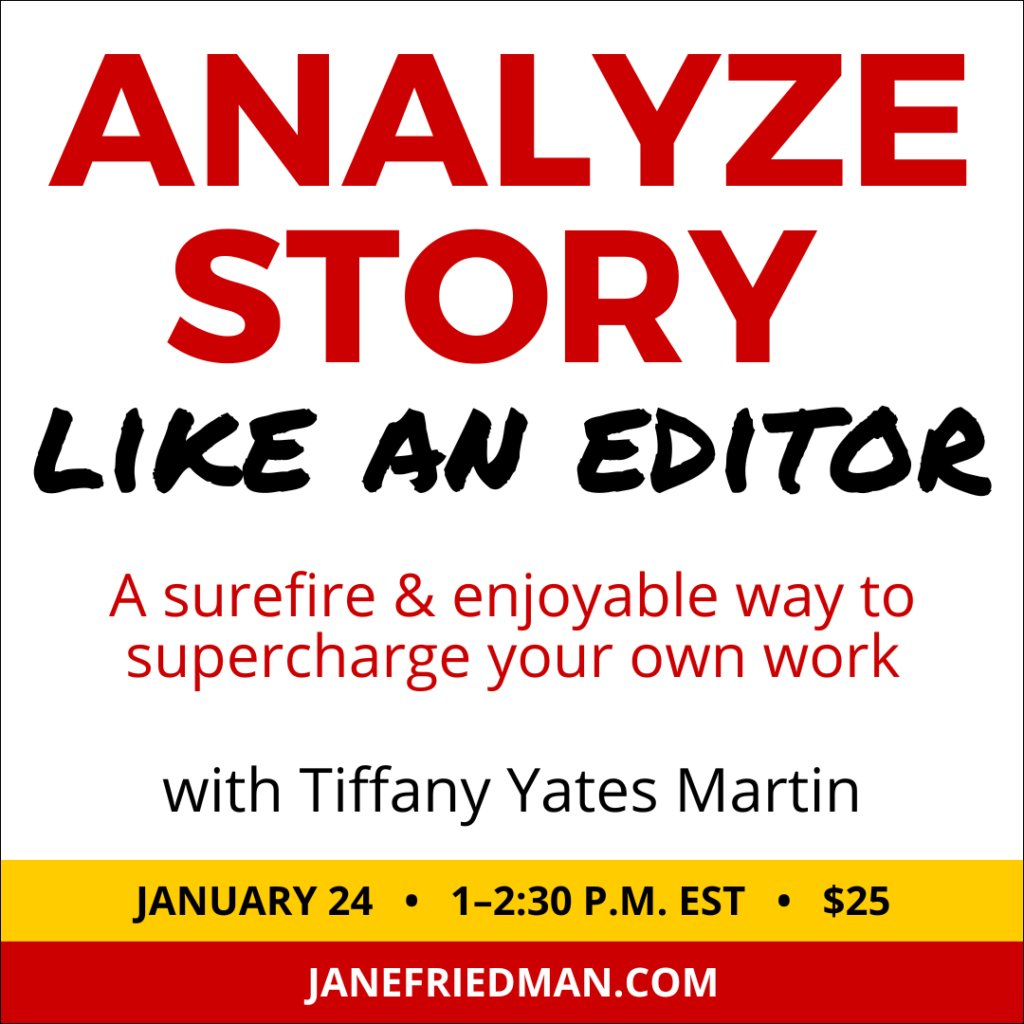

If you nerd out to deep-dive analyzing story like this—or want to learn to, for the extraordinary depth of insight it can offer for your own storytelling—join me and Jane Friedman Weds., January 24, from 1 to 2:30 Eastern, for my live online webinar “Analyze Like an Editor,” one of the most popular—and arguably useful—courses I teach. ($25 with playback for registrants.)

10 Comments. Leave new

Defo gotta watch this now! Sounds fab – love your onion and flavours description!

It’s REALLY good–it continues to develop new tentacles of story and perspective and just keeps surprising us and drawing us in. It’s fascinating storytelling–could have been so dry in a lesser screenwriter’s hands. Thanks, Syl!

Fascinating, but tricky to have the main pov character not sharing internal thoughts! This technique was used in The Silent Patient psychological thriller to great effect. It probably only works with multiple povs providing perspectives.

It is tricky–it can easily slip into feeling coy, cryptic, or manipulative and leave readers unengaged or resentful. I agree that the screenwriters of The Staircase sidestep that partly by using so many other perspectives, and it’s also partly a function of the story itself and its genre–in a mystery or thriller, the not-knowing is a core part of the premise. Their specific techniques may not work for every story or genre, but the idea of adding/revealing facets through considering various perspectives can apply to many. Thanks for the comment, Rebecca!

Hello Tiffany. I have a question. Your post focuses on The Staircase, a fictionalized mini-series that features well-known film stars. The series is based on an earlier French documentary mini-series. Both appear to be technically sophisticated, and they sound like intriguing TV. My question is this: How is a fiction writer, not a TV or film script writer supposed to make practical use of this material? Video is used more and more to make points for fiction writers, but I am beginning to question the practice. It seems to me like apples and oranges, or even applies and potatoes. What do you think?

Thought-provoking comment, as always, Barry.

You know me well enough by now to know that I think story is story–and everything story can be analyzed to help shed light on our writing and storytelling. I agree that it’s not always apples-for-apples, but it is much more often than not, in my view, at the core.

Here, for instance, I’m analyzing the use of different perspectives and the structure and style of the storytelling itself to draw observations about writing stories on the page. As much as I’m using a screen medium here to do it, I could as easily have done it with something like Ann Napolitano’s Dear Edward, which uses a similar varied perspective in the plane-crash parts of the story. Or Brit Bennett’s The Vanishing Half, which does that and also conceals some of the main characters’ motivations from us, and shows them mostly through the eyes of other characters, and weaves together many threads of backstory to unspool the main story.

I know there are some schools of thought that no other medium is applicable to writing as far as analyzing the storytelling, but I don’t feel that way. I analyze fiction and nonfiction; movies and TV shows; podcasts and feature articles and interviews; commercials, songs, poems; company slogans and taglines; even my own life (and others’!). I’ve analyzed magazine articles, family dinners, home owners’ association dramas, and the infamous Oscar slap.

There’s so much we can learn for our own stories from other people’s–no matter the medium. Story is story.

But I respectfully concede that others may feel differently. 🙂

Thanks very much for your follow-up remarks. I suppose it’s because I hold great actors and directors and cinematographers in such high regard that I stick to my point of view. The novelist, or the memoirist or the historian must find the right words that will turn her characters into great actors, and she must do it all by herself (with of course help from a great editor).

I’m a big movie lover too–all my life. And you’re right about the challenges of writing relative to filmmaking–I always say that authors must be screenwriter, actors, director, cinematographer, set designer, costumer, and every other role.

Fascinating dissection. I haven’t watched ‘The Staircase’ and still there are so many takeaways and fodder for nerd dives in what you’ve shared.

I believe that there are common touchpoints in our evolutions as storytellers. Early on we learn to ask ourselves ‘does this character SERVE the story?’ and then we grow to asking ‘does this character STRETCH the story?’ Your words, ‘what we are told and shown, and through whose eyes, with what slant.’ is illustrative of potential to stretch and expand story.

Your observation; ‘I have a feeling viewers are never going to definitively know whether Peterson actually killed his wife.’

Early in my learning process as a mystery writer I feel into the trap of believing that the desire to know who killed the person found dead on page two was enough to keep the reading turning pages until the end. But really now, if it was that simple, all the reader would do is read page two then skip ahead to the last pages. Mission accomplished.

My current approach is that the murder itself is but a mere device. A point of entry into an interconnected web of personalities, relationships, dependencies and goals. So we have X number of characters, each trying to make their way through their current life situation, encumbered by choices already made, in pursuit of their unique wants, and now someone in their orbit is found with his head bashed in, and/or someone in their orbit may have been the basher, and/or the the event presents opportunities or risks to each of these characters. The concentric circles flowing outward from a corpse thrown into a previously still pond. Our attention is held by the ripples long after the unfortunate corpse has settled to the bottom and out of view.

At some level within the mystery genre the single POV, be it first or third person, of the detective / armature / cat, whatever, unraveling the murder is in itself is a contrivance. That character can exist only as the reader’s admission into the world of the murder. Story is one of the few things where what was first coined in the mind bending world of quantum physics as the observer effect (the act of observing will influence the behavior of the thing being observed) can be suspended if the writer wants it to be.

But when it comes to the characters observed by the reader through the lens of that POV . . . for everything a person does there are three reasons; the reason they tell other people, the reason they tell themselves, and the real reason. We read what the character opts to reveal. We learn more about the character via other means and see their revelations in the context of what we believe to be their goals. That knowledge can make us question the calculations behind their words and actions. Then the onion is pealed further and as our awareness grows we question our assumptions about what we believed to be their goals. Give the reader reason to believe A, then believe B, then reconsider A, and do it without the whiplash effect of too much too fast or the resentment of being mislead. Even as being mislead may be what the reader wants. Therein lies mastery.

As I read your examples from ‘Staircase’ in reference to the DA and his personal ax to grind against Michael, the thought that flashed through my mind was ‘how about tossing in some indications that the DA maybe feels trapped in his career path, left criminal law to appease his wife, feels poorly suited for the work of a DA, resents what Michael has written because it cuts too close to the truth he tries to avoid facing. But his marriage is seen to be circling the drain, and with it goes his reason to persist in a job he dislikes. He questions if the defense mechanisms triggered by Michael’s columns have distorted his thinking EVEN as solid evidence against Michael builds.’ It goes on and on. Limited only by considerations of when does the weight of complexity collapse the structure built to support it.

The novel I’m currently shopping around, sometime back when I told a non-writer friend that I’d finally figured out who the killer was (this was at 85K words) he was ‘how could you write that much without knowing?’ Uh, because it was never about the murder, it was about everything swirling around it.* The challenge, for me at least, isn’t writing so many words without knowing who killed her, but narrowing down to the relatively few words that make best use of the infinite possibilities, gains, and losses unleashed by her death.

*Quirks of the trade. One person will love the process and have the abilities to write a mesmerizing, insightful book centered on a woman discovering her husband’s two decades of infidelity. I prefer writing about the women from his past turning up dead.

This comment is packed with gems, Garry. You’re clearly a character-centered writer; that’s my favorite part of story too, and what I think is the heart of it, for the reasons you state: If it were just about figuring out the plot, a synopsis would be as entertaining as a full story. I agree that it’s all the hows and whys that draw us in. Love your example of the DA and how your mind starts creating backstory for him. 🙂 Hazard of the writer’s soul…constantly analyzing human behavior, which I find endlessly fascinating.

Thanks for sharing your insights–great stuff. And if you see The Staircase I’d love to hear your thoughts!